Generating Conditional Names Using RNNs, Transformers, and MoE Models

Introduction: The Quest for Original Names

Ever struggled to come up with a unique name for a character, a place, or a product? I certainly have. Whether it’s naming a new library, a project, or a character, finding appropriate names that don’t sound too bland or too flashy can be challenging.

I am aware there are many tools, both online and offline, that serve this purpose. Nevertheless, this simple yet fascinating problem prompted me to explore methods for generating names on my own.

Existing Methods: What’s Out There

We can separate between traditional and ML-based methods.

Traditional methods, like database lookups or template-based generation, often leave us with repetitive or nonsensical names.

A static database lookup makes name generation as realistic as it gets, but it comes with some additional problems. First, you need a list of curated names. Curated means they have to be of high quality (standardized format, verified information) and they have to represent the sampling space very accurately. If you have to switch generation contexts frequently (e.g., different language, location, etc.), you probably don’t want to do that.

More advanced approaches allow generating new names by exploiting the known rules and/or components of a language. Markov Chains, for example, are a famous statistical learning approach based on autoregressive generation. Template-based generation combines known language elements (e.g., syllables) according to known composition rules (e.g., “vowel after consonant cluster”) to form completely new names. If you can formalize the generation rules well, these approaches can produce interesting results. However, unless you want to dig deeper into formal grammar stuff and so on, each time you want to set up a new generation scenario, you probably do not want to go in this direction.

From the machine learning world, Large Language Models (LLMs) are very interesting candidates for this problem, having the clear advantage of being trained on extremely large quantities of data, being able to produce an output in a flexible/directionable manner through prompting and generation parameters. But to be good enough, they are so computationally demanding that they practically always require an third-party API, which in some contexts may open endless discussions about copyright, privacy, security, and so on. They also work really well with scenarios they have been trained on, but really lag behind when you leave for uncharted territory.

Example 1: common LLM generation scenario (Surnames)

Prompt:

> Generate six surnames of Italian people starting with the following letters C, H, I, D, P, S

Response:

Selecting surnames for Italian lineage. Considering Colombo, Hercolani, Iannone, Donadoni, Pavarotti, and Sforza for diversity.

Here are six Italian surnames, each starting with the letters you provided:

C → Colombo

H → Hercolani

I → Iannone

D → Donadoni

P → Pavarotti

S → Sforza

No comment, looks good.

Example 2: less common LLM generation scenario

Prompt:

> generate me a list of 6 Tengwar names according to the following rules:

(long list of rules of Tengwar)

...

Response:

Here are six Elvish (Tengwar) names using the provided Unicode standard:

Eäron (U+E010 U+E04A U+E023 U+E01C U+E014)

Lindëa (U+E01A U+E010 U+E013 U+E04E U+E025)

Calmindor (U+E002 U+E01A U+E011 U+E010 U+E019 U+E014)

Vanyalótë (U+E015 U+E016 U+E01A U+E022 U+E01C U+E04E U+E00A)

Aranel (U+E019 U+E01C U+E010 U+E014 U+E01A)

Mithrandir (U+E011 U+E008 U+E01C U+E019 U+E004 U+E010 U+E014)

Not being an expert in Tengwar, I would give the benefit of the doubt and assume it works fine (LLM is most likely trained on the language).

Example 3: completely made-up LLM generation scenario:

Prompt:

> generate me a list of 6 Elvish names according to the following rules:

Character map

U+E001 -> E011 Miscellaneous letters

U+E012 -> E023 Punctuation

U+E024 -> E058 Consonants

U+E050 -> E053 Vowel signs

U+E055 -> E057 Additional vowel signs

U+E058 -> E059 unassigned

letters: xyzabcdef

numbers: 12345

diacritics: äüöšž

Rules:

- each name must have at most 3 diacritics, and at least 1

- diacritics can only appear in the even positions

- numbers are only at the second to last position

- vowels after consonants or consonant groups. Only the following consonant groups are allowed: bc, fd, df, cb, cc . If the vowel comes after a consonant group if cannot be a diacritic. Only exception is cbä

- no double letters allowed, also in different parts of the word

Do not lookup additional information online.

Response:

>> Here are six Elvish names following your specified rules:

Xäbcö3d

Bfö1yzä

Düfdä4c

Ccäx2ab

Yüdfö5b

Zäcbä3d

Most names do not follow the grammar constraints we specified. Diacritics are repeated, numbers are in positions different from what the grammar prescribes, and there are repeated letters and forbidden consonant combinations.

The same problem appears even if we provide a “dataset” of valid names (which is not equivalent to “training” the network, but in the lack of model access, is the best we got).

Looking for Alternatives

The LLM has clearly some downsides, but its main limitation comes from the lack of exposure to valid data during training.

But what if we could harness the power of a language model, able to generate names that are diverse yet very realistic, without having to rely on an external service? And being able to control and operate the generation process completely, without the risk of sharing information and/or incurring high processing fees?

Let’s dive into building such a local name generator. We will explore how Recurrent Neural Networks (RNN) and other deep neural architectures can help us create names that stand out. My code originates (and deeply extends) this Pytorch tutorial, which I should mention for fairness, and you may want to check out before starting. I will also use the training data referenced there, i.e. a dataset of last names grouped by language.

# taken from the file "Italian.txt"

Abandonato

Abatangelo

Abatantuono

Abate

Abategiovanni

Abatescianni

Abbà

Abbadelli

Abbascia

Abbatangelo

Abbatantuono

Abbate

...

Why RNNs and LSTMs? Aren’t They Like Super-Obsolete? 👴🏼

Sure, transformers are the new cool kids on the block. Being the fundamental building block of almost all modern LLMs, they have proven to be a valid alternative for most language-related tasks. But RNN and related approaches, such as Long Short-term Memory (LSTM), and Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) cells, still have their charm when it comes to sequence generation tasks. These models are simpler and can be more efficient for certain applications. Plus, they provide a solid foundation for understanding more complex models.

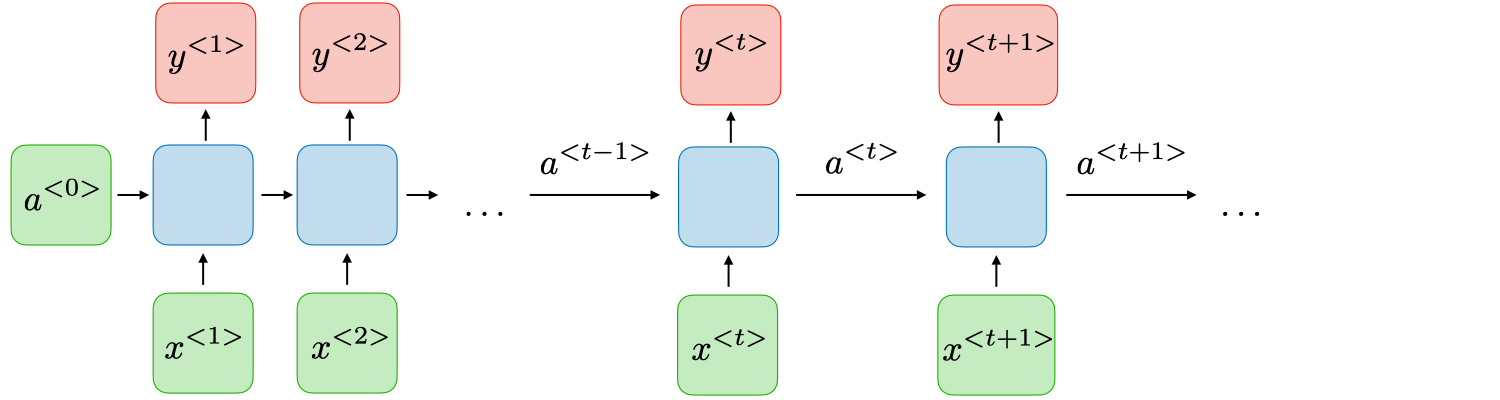

I will not go into the detail of how RNNs work, but you can find a very explanatory tutorial here. The key point is that RNNs process inputs sequentially, by feeding one language unit (be it a token, a word, or character) at a time. The output of the time step t depends on all previous inputs 1 to t as well as on the hidden state 1 to t generated during the previous t-1 iterations. In this way, RNNs learn to memorize important features about the previous step generations which allow taking more accurate decisions in the current time steps.

Approach

The full code is available here: https://github.com/paolo-notaro/name-generator

The approach is fairly simple. It is based on the following assumptions:

- Since we want to generate a short string, it makes sense to use character-level generation. Our tokens will be the valid characters of the target alphabet.

- We have at our disposal a somewhat large database of reference names. For the purpose of this experiment, I used the original data from the Pytorch tutorial. Because the names in the database already encode the grammar of the language, no external rules are necessary.

- We want to conditionally generate our names based on the user input. For this purpose, a “category” label is defined in our database, which can represent e.g., language, gender, location, etc. The label is provided as input to the model.

- We want to be able to train and use the model for inference in a simple computing environment, such as a laptop or a phone. We can use GPUs for speed up training, but they are not deemed necessary here.

Here’s how to do it:

Step 1: Data Preparation

We start by loading and processing the data, converting names to ASCII and creating one-hot encodings.

Our alphabet is composed of N_a=59 different tokens, corresponding to the valid ASCII letters + some punctuation symbols.

Our category set is composed of N_c=18 different categories, corresponding to the language of the names in the training set.

These include (amongst others) English, Italian, German, French, Spanish, Chinese.

# define the valid characters for generation

all_letters = string.ascii_letters + " .,;'-"

n_letters = len(all_letters) + 1 # plus EOS marker

# Read a file and split into lines

def read_lines(file_path: str):

lines = open(file_path, encoding="utf-8").read().strip().split("\n")

return [unicode_to_ascii(line) for line in lines]

...

def load_files(names_data_path: str):

# Build the category_lines dictionary, a list of lines per category

category_lines = {}

all_categories = []

for filename in find_files(names_data_path):

category = os.path.splitext(os.path.basename(filename))[0]

all_categories.append(category)

lines = read_lines(filename)

category_lines[category] = lines

if len(all_categories) == 0:

raise RuntimeError(

"Data not found. Make sure that you downloaded data "

"from https://download.pytorch.org/tutorial/data.zip and extract it to "

"the current directory."

)

return category_lines, all_categories

category_lines contains the list of names, grouped by category.

all_categories is a list of all valid categories.

Step 2: Model Definitions

Next, we define our models, each with its unique architecture.

I implemented the following RNN models to generate names:

- Vanilla RNN “Elman” network

- LSTM network (paper)

- Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) network

For comparison, I also implemented:

- a Transformer-based model, with an encoder-based architecture (paper)

- a Mixture of Experts (MoE), with Multi-layer Perceptron (MLP) as expert models.

Each model implements the forward and init_hidden function.

This second function is required in RNNs to reset the hidden state of the previous generation. If the hidden state is not reset, the model will by default “remember” how to continue based on the previous inputs.

The model outputs log-probabilities of shape B x L x N_a, B being the batch size, L the sequence length.

The model gets rewarded or penalized based on the log-probability of the “correct” token (i.e., the one specified by target_line_tensor):

The loss function used is NLLLoss (see docs).

As a reference, the vanilla RNN code looks like this:

import torch

import torch.nn as nn

class RNN(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, input_size, hidden_size, output_size, n_categories):

super(RNN, self).__init__()

self.hidden_size = hidden_size

self.rnn = nn.RNN(n_categories + input_size, hidden_size, batch_first=True)

self.o2o = nn.Linear(hidden_size + input_size, output_size)

self.dropout = nn.Dropout(0.1)

self.softmax = nn.LogSoftmax(dim=2)

self.num_directions = 1

def forward(self, category, input_tensor, hidden):

input_combined = torch.cat(

(category, input_tensor), dim=2

) # Concatenate along the feature dimension

output, hidden = self.rnn(input_combined, hidden)

output_combined = torch.cat((output, input_tensor), dim=2)

output = self.o2o(output_combined)

output = self.dropout(output)

output = self.softmax(output)

return output, hidden

def init_hidden(self, batch_size=1):

return torch.zeros(self.num_directions, batch_size, self.hidden_size)

You can find the rest of the models’ implementation here.

Step 3: Training the Models

We train the models using a training script and log the results with MLflow. The process works like this: we sample a category for generation, we sample a name in that category, and we split the name into tokens. Then, for each time step, we predict the next token in the sequence, so that the model can generate names character-by-character in an auto-regressive manner.

First, we set up some batch loading functions.

There are three main inputs for each training sample:

- the input characters (

input_line_tensor), of shapeB x L x N_a,Bbeing the batch size (provided by the user at runtime),Lbeing the word length (padded to the maximum length in the batch for consistency and allow concatenation), andN_athe alphabet size as above. The character indices are one-hot encoded (i.e., ifAis index 3, then we place a 1 in position 3:[0 0 0 1 0 0 0 ...]) - the target characters (

target line tensor) of shapeB x L. It looks like the input characters, shifted by one char to the right (e.g.,"P A O L O"–>A O L O /s,/send of generation token). However, it is not one-hot encoded (theNLLLossfunction requires the raw index). - the category input (

category_tensor) of shapeB x L x N_cis a one-hot encoded vector of the category of the name, repeated L times to be fed at each time step along with the input characters.

import torch.nn.utils.rnn as rnn_utils

from torch.optim import Adam

from tqdm import tqdm

from utils import (

VALID_LOSSES,

input_tensor,

random_choice,

target_tensor,

to_one_hot,

)

# Get a random category and random line from that category

def random_training_pair(all_categories, category_lines):

category = random_choice(all_categories)

line = random_choice(category_lines[category])

return category, line

# Make category, input, and target tensors from a random category, line pair

def random_training_example(all_categories, category_lines):

category, line = random_training_pair(all_categories, category_lines)

cat_tensor = to_one_hot(category, all_categories)

input_line_tensor = input_tensor(line)

target_line_tensor = target_tensor(line)

return cat_tensor, input_line_tensor, target_line_tensor

def random_training_batch(all_categories, category_lines, batch_size):

category_tensors = []

input_line_tensors = []

target_line_tensors = []

for _ in range(batch_size):

category, line = random_training_pair(all_categories, category_lines)

category_tensors.append(to_one_hot(category, all_categories))

input_line_tensors.append(input_tensor(line))

target_line_tensors.append(target_tensor(line))

category_tensor = torch.cat(category_tensors, dim=0)

input_line_tensor = rnn_utils.pad_sequence(input_line_tensors, batch_first=True)

target_line_tensor = rnn_utils.pad_sequence(target_line_tensors, batch_first=True)

# repeat category tensors L times to match pad sequence length

sequence_length = input_line_tensor.size(1)

category_tensor = category_tensor.expand(

batch_size, sequence_length, category_tensor.size(-1)

)

return category_tensor, input_line_tensor, target_line_tensor

Then we define our main training logic.

We organize our training into iterations. During each iteration, a random batch of names is loaded, converted to a tensor object, and fed into our neural network. The output scores are used to compute the loss function. We also define and use Adam as our optimizer.

def train_iteration(

model,

optimizer,

criterion,

category_tensors,

input_line_tensors,

target_line_tensors,

):

batch_size = len(input_line_tensors)

hidden = model.init_hidden(batch_size)

model.zero_grad()

output, hidden = model(category_tensors, input_line_tensors, hidden)

loss = criterion(output.view(-1, output.size(-1)), target_line_tensors.view(-1))

loss.backward()

optimizer.step()

return output, loss.item()

def train(model, args: Namespace, all_categories, category_lines):

"""Train the model while logging with MLflow."""

mlflow.set_experiment(args.experiment_name)

model.train()

model_size = sum(p.numel() for p in model.parameters())

print(f"Model size: {model_size}")

with mlflow.start_run(

run_name=f"{args.architecture}-{datetime.now():%Y-%m-%d-%H-%M-%S}"

):

# Log hyperparameters

mlflow.log_param("architecture", model.__class__.__name__)

mlflow.log_param("hidden_size", args.hidden_size)

mlflow.log_param("learning_rate", args.learning_rate)

mlflow.log_param("n_iterations", args.n_iterations)

mlflow.log_param("loss_type", args.criterion)

mlflow.log_param("batch_size", args.batch_size)

mlflow.log_param("model_size", model_size)

all_losses = []

total_loss = 0.0

loss_fn = VALID_LOSSES[args.criterion]

optimizer = Adam(model.parameters(), lr=args.learning_rate)

start = time.time()

for i in (pbar := tqdm(range(1, args.n_iterations + 1))):

category_tensors, input_line_tensors, target_line_tensors = (

random_training_batch(all_categories, category_lines, args.batch_size)

)

_, loss = train_iteration(

model,

optimizer,

loss_fn,

category_tensors,

input_line_tensors,

target_line_tensors,

)

total_loss += loss

mlflow.log_metric("loss", loss, step=i)

pbar.set_description(f"{loss=:6.4f}")

if i % args.plot_every == 0:

avg_loss = total_loss / args.plot_every

all_losses.append(avg_loss)

mlflow.log_metric("avg_loss", avg_loss, step=i)

total_loss = 0

training_time = time.time() - start

mlflow.log_metric("training_time", training_time)

model.eval()

print(f"Training complete: {training_time:.2f}s. Saving model...")

return all_losses

Step 4: Running the Training Script

We use a CLI to specify training parameters and start the training process.

We train for 100000 iterations with batch size 32. Here is the training script:

from argparse import ArgumentParser

from datetime import datetime

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import mlflow

import torch

from training import train

from utils import (

VALID_ARCHITECTURES,

VALID_LOSSES,

load_files,

n_letters,

random_experiment_name,

)

def parse_train_args():

parser = ArgumentParser(description="Train the RNN model with MLflow logging.")

parser.add_argument(

"-e",

"--experiment_name",

type=str,

required=False,

default=random_experiment_name(),

help="MLflow experiment name",

)

parser.add_argument(

"--hidden_size", type=int, default=128, help="Size of RNN hidden layer"

)

parser.add_argument(

"--learning_rate", type=float, default=0.005, help="Learning rate"

)

parser.add_argument(

"-n",

"--n_iterations",

type=int,

default=100000,

help="Number of training iterations",

)

parser.add_argument(

"-b", "--batch_size", type=int, default=1, help="Batch size for training"

)

...

return parser.parse_args()

def main():

args = parse_train_args()

mlflow.set_tracking_uri("file:./mlruns") # Local MLflow tracking

print("Loading data...")

category_lines, all_categories = load_files("data/names/*.txt")

print("Preparing model...")

# load model

if args.model:

model = torch.load(args.model, weights_only=False)

model.eval()

else:

model = VALID_ARCHITECTURES[args.architecture](

input_size=n_letters,

hidden_size=args.hidden_size,

output_size=n_letters,

n_categories=len(all_categories),

)

# start training

time_start = datetime.now().strftime("%Y-%m-%d_%H:%M:%S")

save_model_path = (

args.save_model_path

if args.save_model_path

else f"models/{args.architecture}_{time_start}.pt"

)

print("Training model with MLflow tracking...")

all_losses = train(model, args, all_categories, category_lines)

# save model

torch.save(model, save_model_path)

mlflow.log_artifact(save_model_path)

# show loss plot

plot_loss(all_losses, args.architecture, time_start)

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

Evaluation and Results

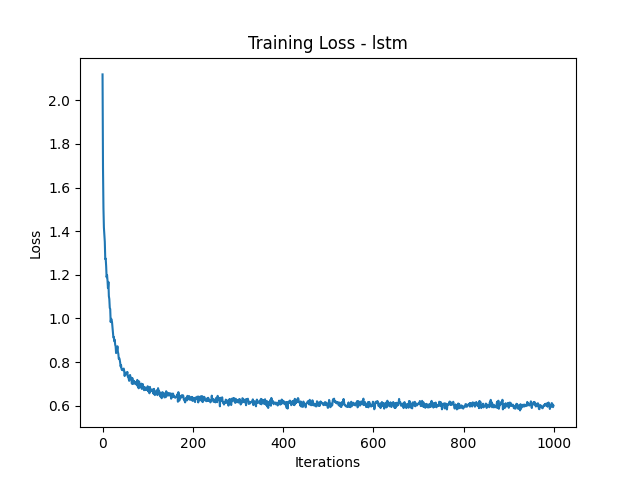

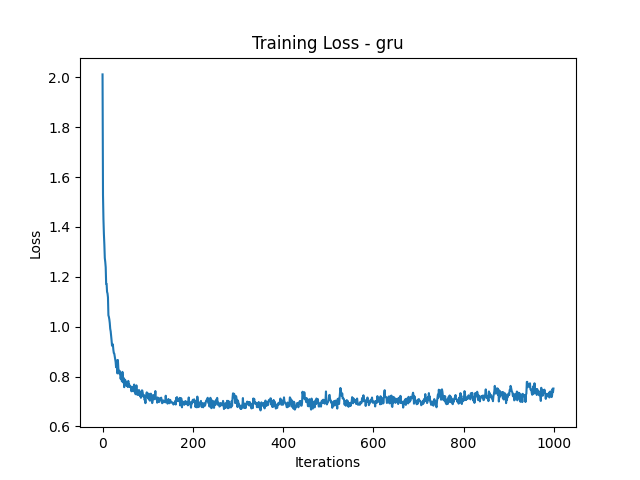

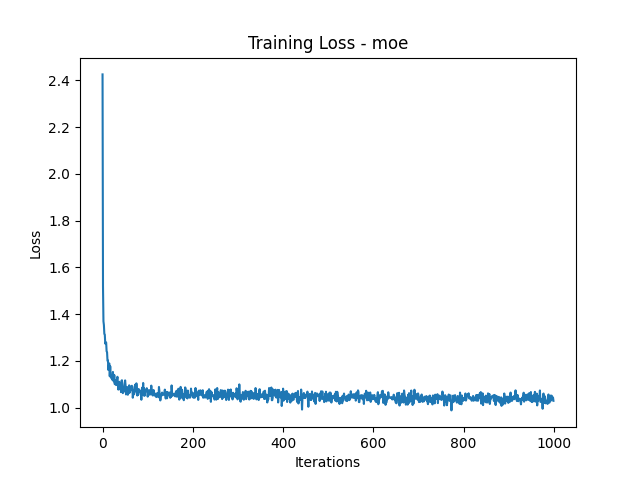

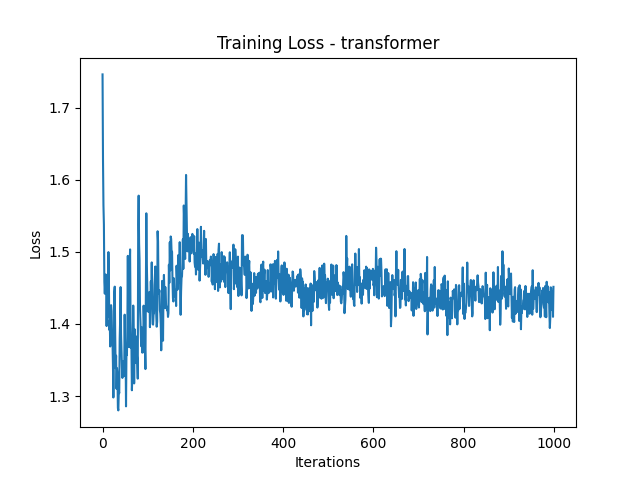

We evaluate the models by plotting the training loss and generating names.

We generate three names for each category of the following categories: RUS=Russian, GER=German, ESP=Spanish, CHI=Chinese, ITA=Italian. Here is the evaluation script:

from argparse import ArgumentParser

import torch

from utils import (

all_letters,

input_tensor,

load_files,

n_letters,

to_one_hot,

)

# Sample from a category and starting letter

def sample(model, category, all_categories, start_letter="A", max_length=20):

with torch.no_grad(): # no need to track history in sampling

cat_tensor = to_one_hot(category, all_categories)

input_ = input_tensor(start_letter)

hidden = model.init_hidden(batch_size=1)

output_name = start_letter

for _ in range(max_length):

output, hidden = model(cat_tensor, input_.unsqueeze(0), hidden)

_, top_i = output.topk(1, dim=-1)

top_i = top_i.squeeze().item()

# end of generation check

if top_i == n_letters - 1:

break

letter = all_letters[top_i]

output_name += letter

if isinstance(model, (RNN, LSTMModel, GRUModel)):

# we only give the next letter as input, hidden memorizes the previous ones

input_ = input_tensor(letter)

elif isinstance(model, (TransformerModel, MixtureOfExperts)):

# we give the whole name as input

input_ = input_tensor(output_name)

cat_tensor = torch.cat(

[cat_tensor, to_one_hot(category, all_categories)], dim=1

)

return output_name

# Get multiple samples from one category and multiple starting letters

def samples(model, category, all_categories, start_letters="ABC"):

for start_letter in start_letters:

print(sample(model, category, all_categories, start_letter))

def parse_evaluate_args():

parser = ArgumentParser(description="Evaluate the generative model.")

parser.add_argument(

"-m", "--model", type=str, required=True, help="Path to a pre-trained model"

)

return parser.parse_args()

def main():

args = parse_evaluate_args()

print("Loading data...")

_, all_categories = load_files("data/names/*.txt")

# load model

print("Loading model...")

model = torch.load(args.model, weights_only=False)

model.eval() # Ensure the model is in evaluation mode

print("Sampling names...")

samples(model, all_categories=all_categories, category="Russian", start_letters="RUS")

samples(model, all_categories=all_categories, category="German", start_letters="GER")

samples(model, all_categories=all_categories, category="Spanish", start_letters="SPA")

samples(model, all_categories=all_categories, category="Chinese", start_letters="CHI")

samples(model, all_categories=all_categories, category="Italian", start_letters="DPS")

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

Here are the loss plots and some generated names:

Loss Plots

Generated Names

| Index | LSTM | GRU | RNN | MoE | Transformer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Robalin | Raidyachin | Ryzhov | Ry | Rlnnn |

| 2 | Ustinsky | Usilev | Usthov | Ubbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbe | Uallr |

| 3 | Shalnov | Shanabanov | Shailin | Stz | Sallr |

| 4 | Grosse | Geissler | Geister | Gheler | Glrnn |

| 5 | Esser | Ebner | Essch | Esesessssssssssssssss | Eens |

| 6 | Rosenberg | Riet | Ross | Riczz | R’rnn |

| 7 | Salazar | Santiago | Sanaver | Spez | Sarnn |

| 8 | Perez | Perez | Peirtez | Pez | P’nnn |

| 9 | Albert | Araujo | Abasca | Atz | Aarnn |

| 10 | Chaim | Chang | Chang | Cz | Clrssaa |

| 11 | Huie | Huan | Huan | Hi | Hlrssaa |

| 12 | Ing | Ing | In | Ie | Ihrssaa |

| 13 | Di pietro | De rrani | Diori | Delererererergergggdd | Dahah |

| 14 | Pavoni | Parisi | Pati | Pererererggggdddddddd | Peahah |

| 15 | Salvatici | Salvaggi | Sarti | Spppppererererergergg | Sahah |

Discussion and Quality Judgegment

The LSTM and GRU models generated the most realistic names, closely followed by the RNN. The MoE and Transformer models struggled, often producing repetitive or nonsensical names. If you’ve ever wanted your next D&D character to be named ‘Bbbbbbbbe the Barbarian’, MoE might have you covered!

To improve name generation quality, we might consider:

- Data Augmentation: increase the diversity and size of the training dataset

- Hyperparameter Tuning: experiment with different hyperparameters, e.g. learning rate and hidden size

- Model Ensemble: combine predictions from multiple models for more robust names

Wrap Up and Conclusion

Takeaways and Lesson Learned

We explored various models to generate realistic names and we were able to build efficient name generation systems for various applications. We showed the versatility and relevance of RNN-based approaches in sequence generation tasks. Exploring different models and techniques enhances our understanding and opens up new possibilities in machine learning.

While newer models like Transformers are powerful, simpler models can still yield impressive results. While building your own local name generator from scratch may seem like reinventing the wheel in an age of advanced LLMs, there’s genuine joy in understanding the nuts and bolts of the full generation process.

Some ideas for future expansion might include:

- Different Datasets: generate names for various categories like places or products

- Hyperparameter Optimization: use techniques like grid search to fine-tune hyperparameters

- Web Application: develop a web app to make the name generator accessible